A Landmark Shift in Global Climate Policy

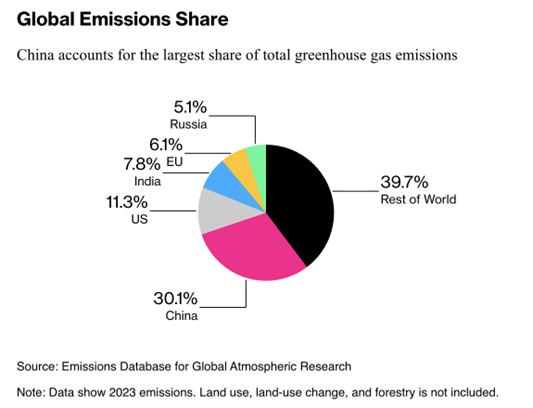

China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG), has announced a landmark shift in its climate policy by committing to its first-ever absolute emissions reduction target. This move, delivered by President Xi Jinping, is a major geopolitical and economic development that carries profound implications for global businesses, supply chains, and international climate diplomacy. This commitment is particularly significant as China accounts for the largest share of total global greenhouse gas emissions. It signals a move away from relying solely on relative reduction targets, which measure emissions per unit of economic output, toward a firm limit on total national pollution.

The New Commitment and The Dual-Path Strategy

President Xi pledged that China would reduce its economy-wide GHG emissions by 7–10% by 2035. This commitment, presented as part of the country’s updated pledges under the Paris Agreement, establishes a hard ceiling on total national pollution. Crucially, Xi framed the target not as a final limit, but as a “floor, not a ceiling,” indicating a potential willingness to implement stronger reductions based on favorable domestic and international conditions. This suggests that China, which has a history of exceeding its initial climate commitments, may pursue deeper cuts if economic or political conditions allow.

This target is supported by a massive investment and policy acceleration into clean technology, reinforcing a dual-path strategy: China plans to expand its solar and wind power capacity to more than six times 2020 levels. This objective solidifies the nation’s position as the global price-setter in green technology and manufacturing, particularly in solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles. Furthermore, the commitment includes policies to ensure “new energy vehicles” (NEVs) become the mainstream in new vehicle sales, driving the accelerated decarbonization of the automotive sector. The plan is also supported by an objective to increase forest stocks to over 24 billion cubic meters. This is a key strategy to utilize forest biomass as a natural carbon sink to sequester atmospheric CO2 and help offset industrial emissions.

Strategic Risk and Geopolitical Dynamics

This pledge creates immediate and long-term strategic challenges for global business professionals and risk managers, particularly concerning global supply chain stability and compliance. The introduction of a hard emissions cap compels all multinational corporations with operations or suppliers in China to commence a definitive and potentially costly journey toward decarbonization. Businesses must anticipate an Increased Transition Risk for carbon-intensive assets and facilities, higher Compliance Costs driven by new, stringent local environmental regulations, and a potential Competitive Disadvantage for those failing to rapidly pivot to clean energy sources. This also implies mandatory energy efficiency upgrades and the risk of asset devaluation for carbon-intensive investments.

Simultaneously, the policy carries significant geopolitical weight. With the U.S. having signaled a second withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under President Donald Trump, China is strategically positioned to assume a greater leadership role in global climate governance. Xi’s commitment and his implicit criticism of the U.S.’s fossil-fuel focus create a new axis where climate policy is inseparable from international trade and foreign policy. This gives Beijing increased leverage in future multilateral negotiations and market access decisions, establishing China’s climate policy as a guiding factor for global business.

However, the most significant and immediate risk factor remains China’s heavy dependence on coal power. Despite the ambitious renewable targets, new coal-fired power plants are still under development, which enjoys strong political support. This reliance creates a profound policy friction and undermines the speed of the transition, forcing businesses to manage the risk of potential stranded assets in traditional energy supply chains.

Global Critique and the 1.5∘C Shortfall

While the absolute target represents a monumental step for China, it has been widely criticized by global climate experts as insufficient to meet international objectives. Analysts contend that a reduction closer to 30% would be necessary for China to align with the Paris Agreement’s most ambitious goal of limiting global warming to 1.5∘C above preindustrial levels. Kaysie Brown of the E3G thinktank stated the target “falls critically short” of global necessity and even China’s own 2060 carbon neutrality goal. The U.N. Secretary-General has also consistently warned that the current collective climate pledges from nations worldwide are insufficient, reinforcing that China’s pledge, while historic, must be viewed in the context of a global effort that still requires nations to go “further and faster”.

Conclusion

In summary, China’s commitment to its first absolute emissions reduction target is a watershed moment that structurally changes the global risk landscape, shifting from vague intentions to defined regulatory limits for businesses operating within its borders. While the initial reduction percentage is deemed inadequate by global climate scientists to meet the 1.5∘C goal, the policy is strategically important for two reasons: it solidifies China’s economic dominance in the clean technology sector, and it enhances its geopolitical leverage in climate governance, particularly as Western engagement wavers. The primary challenge remains the management of the Coal Paradox, the tension between domestic energy security and climate goals, which will be a persistent source of Transition Risk for international energy and manufacturing supply chains.